This is probably the #1 question that people ask when they find out I'm a hurricane researcher, especially now that we live in South Florida. I wish I could provide an exact answer, but unfortunately our science is not at a point where I can answer that question with even moderate confidence.

There are several groups that do seasonal predictions of hurricane activity. NOAA Released Theirs Yesterday. These forecasts account for various things like ocean temperatures in the Atlantic (warmer water tends to favor hurricanes) and ocean temperatures in the Pacific (when the Equatorial Pacific is warm, called "El Nino", the thunderstorms there produce upper level winds that tend to destroy Atlantic hurricanes). This year, there is a weak El Nino, but the Atlantic is also pretty warm, and Western Africa (the area where most Atlantic Hurricanes are born) is also fairly wet, which would favor Atlantic storms. So there are a lot of competing factors, and it's too early to say if this will be a "quiet" or "busy" season.

The thing is, these seasonal forecasts, while quite interesting scientifically, simply predict how many storms will form in the entire Atlantic Basin over the whole season. They don't tell you where the storms will go, or when they will be there. There are researchers that try to assess the landfall risks in their seasonal outlooks (my friends at Weather Tiger are one), but that science is not to the point where we can say with any accuracy whether Miami, or Lakeland, or Tallahassee, or Houston, will be hit by a Category 3 hurricane this season.

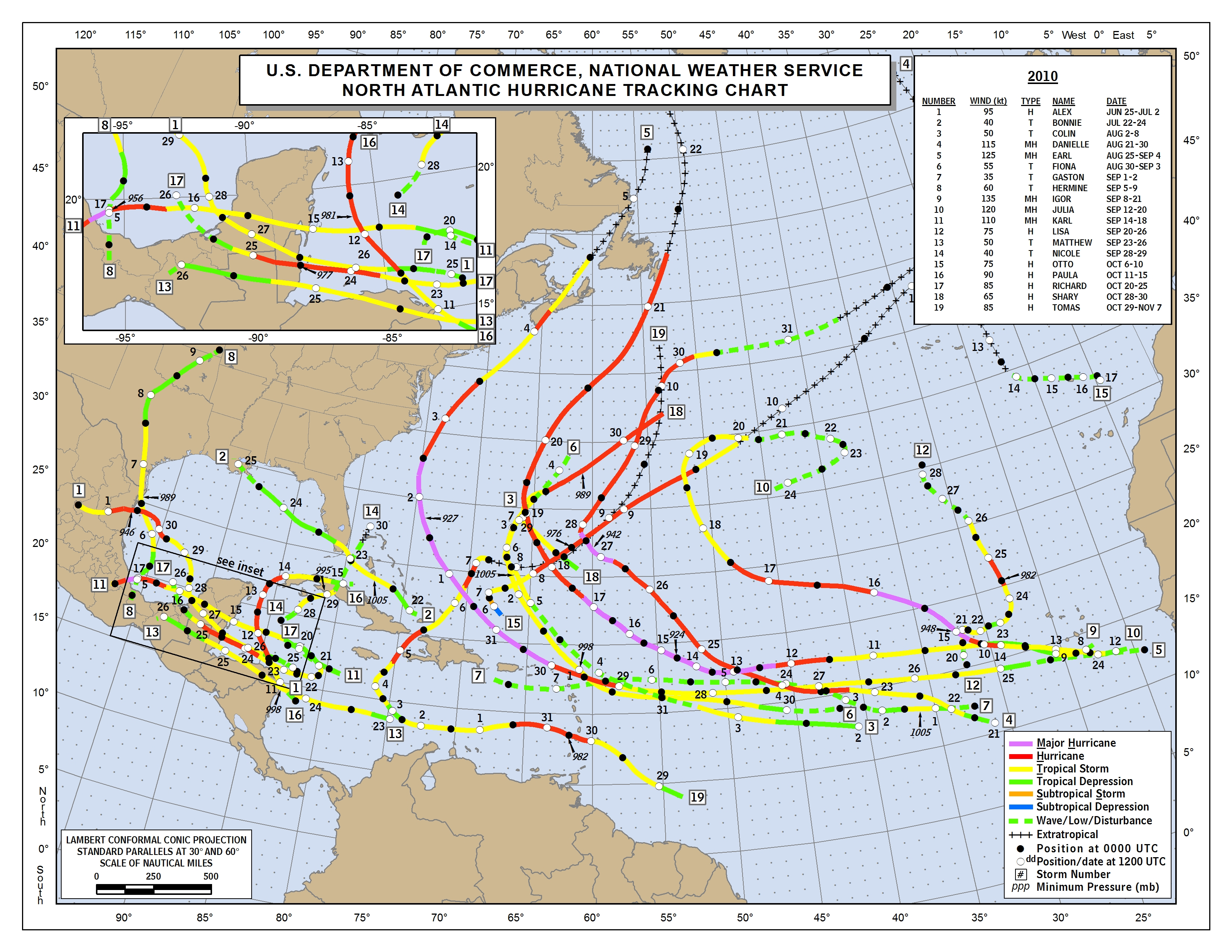

And it doesn't necessarily matter (for landfall risks) whether a season was "busy" or not. 2010 was one of the busiest recent seasons, but almost all big storms avoided the U.S.:

On the other hand, 1992 was one of the most overall inactive seasons in recent history, with only 6 tropical storms and 4 hurricanes:

There was one that hit the U.S., however, known as Hurricane Andrew. One of the worst natural disasters in U.S. history.

So you can see that bad hurricane hits can happen in "active" or "quiet" years. The cliche saying is "it only takes one", and that is quite true.

It's a little depressing to know that we probably won't be able to tell you whether a hurricane could hit your house more than 3-5 days out, but the good news is that you can take this time before the busy part of the season to get ready in case one does come!

Here Are Some Hurricane Preparedness Tips

It's Also Important to Know if You Are in an Evacuation Zone

Hopefully, there won't be any bad hurricane landfalls, whether the Atlantic as a whole has 20 storms or 5, but just be ready either way!